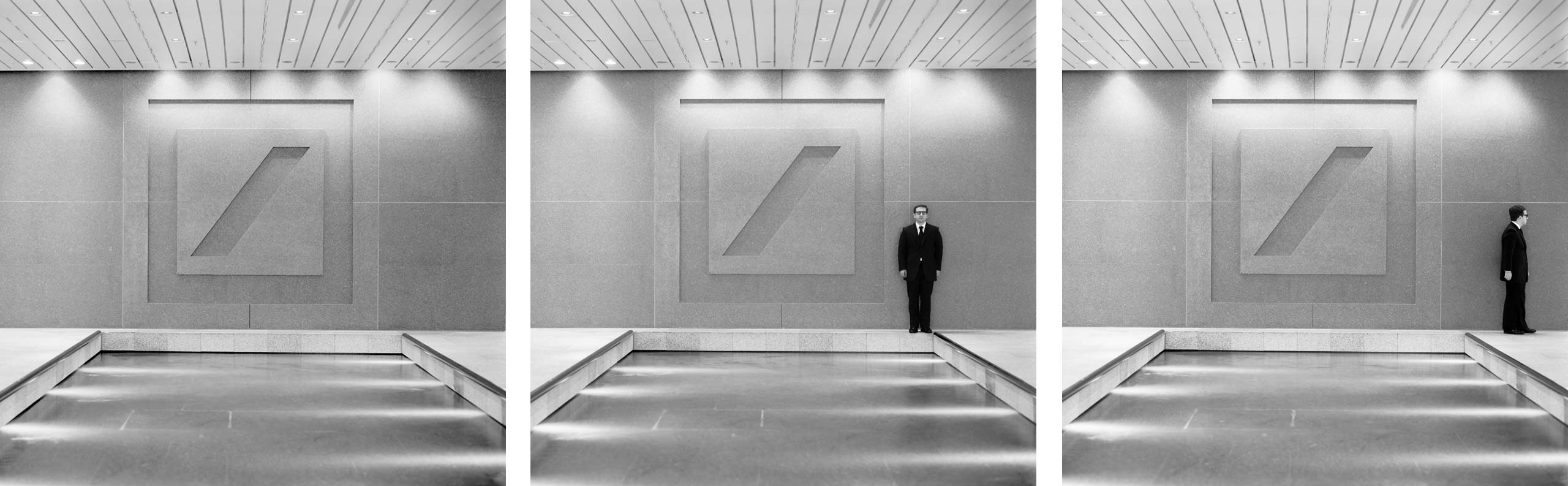

In each of my works, I am the primary material, the sole actor, as well as the historian of the performance. Each of my works consists of at least two images, identical but for the fact that I appear in the second and any subsequent images. I have always been inspired by old cinema, and for that reason, when possible, I gravitate toward producing my work in a larger-scale format that approaches the big screen of the cinema.

I include myself in the images so that I can step into, experience and explore the spaces depicted in my images myself, and then document my performance in the space through photography. All of the spaces that I photograph were created for the purpose of human use and occupation, and my entrance into the frame represents the humanization of the space and allows me to express my specific interpretation of how the space might be experienced.

In each case where I appear in the work, I try to melt into the worlds I portray, but, simultaneously, the insertion of me into the space also completely alters the meaning of the image of the unoccupied space. I believe that the interpretation of the spaces that I invade changes completely through my presence. I replace the viewer’s interpretation of the image with my own. I resume control and force the viewer to participate in the story that I am telling, reminding the viewer that interactivity is merely an illusion of control. To understand my work, like any work of art, the viewer must suspend that illusion and surrender to my vision.

This is just as in everyday life, where we are forced to deal with constantly changing realities. The entrance of any of us into a space creates a new reality. And each new reality is different from any one that came before it, as no reality can be recreated identically a second time.

Spiros Margaris

Photographic works

Silver Gelatin Print or C-prints (face-mounted to Plexiglas using the Diasec process) or C-prints on aluminum or aluminium-dibond laminated

Dimensions

The size varies from work to work, but the general sizes for the works are :

Approximately 120 x 140 cm, in an edition of 3 (or 6) plus two artist’s proofs numbered A.P. I – II

Approximately 80 x 100 cm, in an edition of 3 (or 6) plus two artist’s proofs numbered A.P. I – II

Approximately 60 x 70 cm, in an edition of 3 (or 6) plus two artist’s proofs numbered A.P. I – II

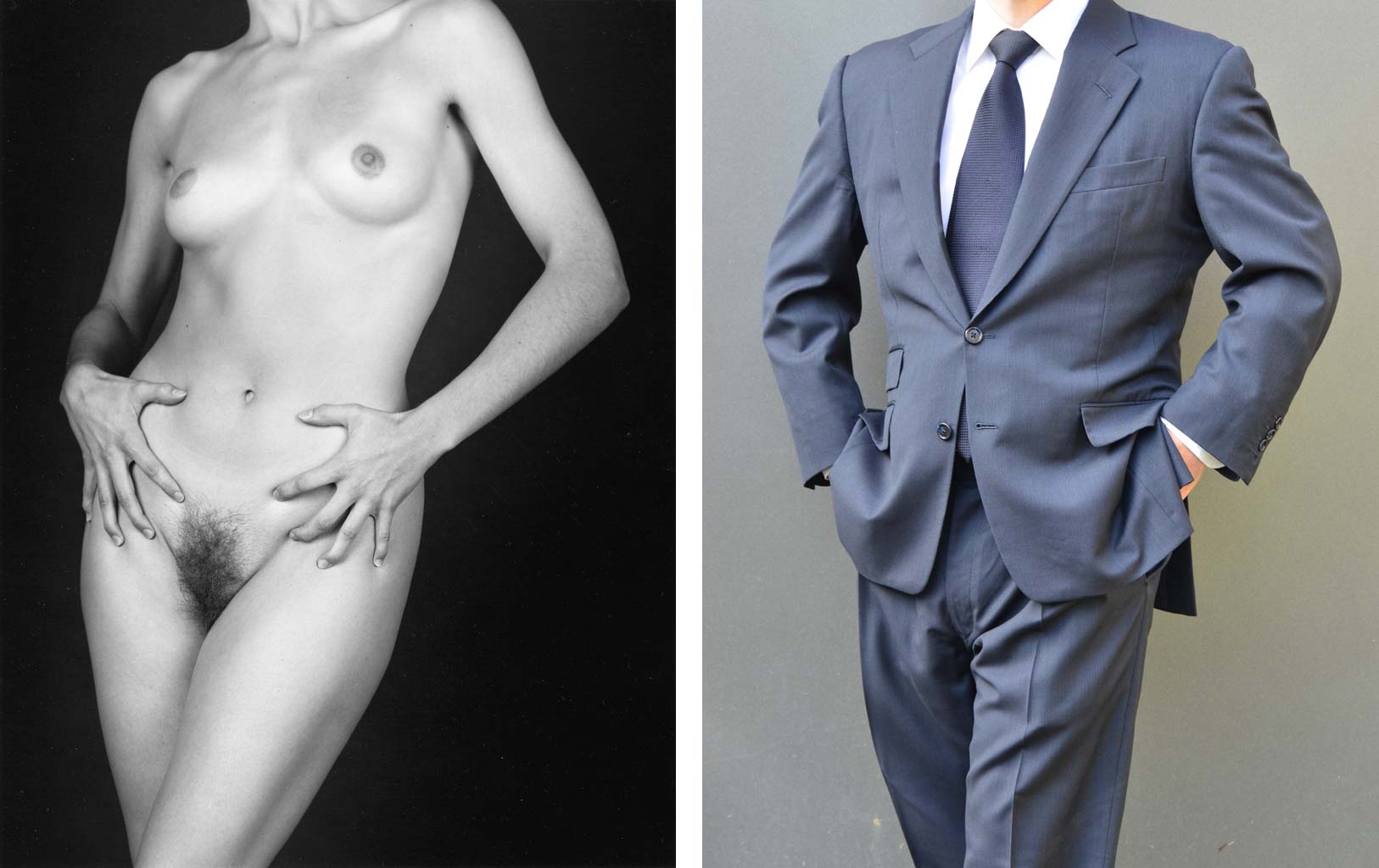

At first sight the nude woman seems vulnerable wearing no protective suit of armour, but she is the stronger sex in my mind. The nude woman has no need to wear a suit of armour to show her strength. On the other hand, the man’s blue suit of armour seems essential to protect his emotional insecurity from damage being inflicted from today’s increasingly complex and confusing world.

Spiros Margaris

Suit of Armour Video

The art series is inspired and based on the films of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up/Blowup (1966) and René Clément’s Plein Soleil/Purple Noon (1960).

The director’s cut is my interpretation of how the film should …

Spiros Margaris

Inspired by a favourite French crime film „Le Samouraï“ (1967) which was directed by French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville.

Melville was a strong influence for the directors of the New Wave, the innovative French film movement.

Spiros Margaris

Inspired by the Italien cartoon character Mr Rossi which was created by animator Bruno Bozzetto.

The title of this series was derived from the feature length Mr Rossi film Mr Rossi’s Dreams (1976) (I Sogni del signor Rossi).

Spiros Margaris

Anmerkungen von Daniel Marzona zu drei Arbeiten von Spiros Margaris – Juni 2002. Daniel Marzona, former Associate Curator, P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center (now MoMA P.S.1), New York.

Spiros Margaris untersucht in seinen Serien Mein Spielplatz, Die Turnhalle und Schulträume die Funktion der Photographie im Hinblick auf ein individuelles Gedächtnis, auf ein persönliches Erinnern. Als Erinnerungsbilder spüren diese Photographien einer Vergangenheit nach und machen doch schlagartig klar, dass diese als bildgewordene Realität im nachhinein nicht mehr zu haben ist. In einer Zeitverschiebung von gut zwanzig Jahren können photographische Bilder das Wesen einer spezifischen Erinnerung naturgemäss nicht objektiviert zum Vorschein bringen, da jede spezifische Erinnerung individuell codiert und konnotiert ist, durchdrungen vom Erleben des Erinnernden. Das heisst, dass die Motive gegebenenfalls für den Künstler den Charakter einer spezifischen Gedächtnisstimulans einnehmen mögen, dass sie gleichzeitig diese Funktion kaum je fur den „unbeteiligten“ Betrachter erfüllen können. In gewisser Hinsicht ist das Projekt also von vornherein zum Scheitern verurteilt. Ein geplantes Misslingen, wie es scheint, da die Photographien erst in ihrem Scheitern an einer vorgeblichen Aufgabe die Bedeutung erlangen, die uns anrührt. Denn es geschieht etwas beim Betrachten dieser wunderbar naiven Serien, die jeweils das nüchterne Bild eines Ortes, sei es ein Klassenzimmer, sei es eine Turnhalle, mit dem selben Motiv inklusive des im Bild anwesenden Künstlers konfrontieren. Verloren wirkt der junge Mann im Anzug, jeglicher Individualität beraubt, scheint er offensichtlich der Zeit entwachsen, deren Erinnerung er beschwört . Eben diese offenkundige Verlorenheit des Mannes in der im Bilde festgehaltenen Umgebung, die seine Kindheit repräsentiert, findet Anschluss an allgemeingültige Gedächtnismuster. Denn obwohl den meisten Menschen unserer von kriegerischer Zerstörung verschonten Generationen die Orte ihrer Kindheit noch unversehrt zur Verfügung stehen, fühlen wir uns zumeist fremd, geradezu entfremdet, sobald wir sie aufsuchen.

Der Anblick einer Photographie aus Kindertagen vermag uns dagegen oftmals emotional stärker in den Bann zu ziehen, als der reale Besuch der abgebildeten Orte in der Jetztzeit. So offenbaren die Serien Spiros Margaris‘ ganz im Einklang mit den Ideen von Roland Barthes, dass Photographien die Erinnerung an bestimmte, längst vergangene Ereignisse auf ähnliche Weise beflügeln können, wie der von Marcel Proust beschriebene Geruch und Geschmack eines in Kindertagen genossenen Gebäcks. Gleichsam zeigen sie jedoch, dass sich diese Funktion der Photographie nicht nachträglich konstruieren und vor allem nicht objektivieren lässt.

In seinem Buch „Die helle Kammer“ versucht Barthes die Magie der Photographie mit dem Satz „So ist es gewesen“ zu charakterisieren. In ihrer Rückführbarkeit auf eine unhintergehbar vergangene Wirklichkeit liege die Faszination jeder Photographie. Des Weiteren weist Barthes der Photographie einen subjektiven und einen objektiven Gehalt zu, wenn er vom Punctum und Studium der Photographie spricht. Zu den Photographien Spiros Margaris‘ liesse sich anmerken, dass ihr Geheimnis nicht in ihrem „So ist es gewesen“ begründet sein kann, da sich die vergangene Wirklichkeit in diesen Bildserien unmittelbar als eine konstruierte Gegenwart herausstellt. Die tiefere Bedeutung kommt den Bilder demgegenüber dadurch zu, dass sie trotz aller Melancholie und Sentimentalität unmissverständlich zeigen, dass eine Vergangenheit atmosphärisch nicht über den Weg einer topographischen Rekonstruktion in der Gegenwart zu vermitteln ist. Nun beginnen wir also zu ahnen, warum der Künstler so traurig und verloren wirkt. Er kann sich den Orten seiner Kindheit im Bild nicht anverwandeln, die angestrebte Annäherung an das vergangene Glück oder Unglück misslingt. In den Bildern verschmilzt das Punctum untrennbar mit dem Studium, die angestrebte subjektive Wiedererinnerung einer Vergangenheit geht in der konstruierten Gegenwart nicht auf.

Direkt nach der Erfindung der Photographie, in den 50er Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts, schwärmten mit einer Kamera ausgerüstete Mitarbeiter der „Historischen Kommission“ zu Dutzenden in ganz Frankreich aus, um Kirchen und andere vom Verfall bedrohte Bauwerke zu dokumentieren. Ihre Mission war durchaus von Erfolg gekrönt, schliesslich trugen sie in weniger als fünfzehn Jahren einige tausend Photographien zusammen, die jeweils sorgsam archiviert wurden. So lieferte die Photographie bereits wenige Jahre nach ihrer Erfindung ein unschätzbares Instrument der Denkmalpflege und der architekturgeschichtlichen Forschung und wurde gleichsam in den Apparat des gesellschaftlichen Gedächtnisses integriert.

Die Bildserien von Spiros Margaris verdeutlichen auf humorvoll-betrauernde Weise, den Unterschied zwischen universellem und individuellem Gedächtnis, indem sie einem Medium, nämlich der Photographie, eine Aufgabe übertragen, die es nicht zu leisten vermag. Erinnerungen sind eben luftiger, verschwommener als Bauwerke und haben keine Topographie, die sich photographisch dokumentieren liesse. Ebenso wie Träume entziehen sich Erinnerungen, sofern sie nicht gesellschaftlich ritualisiert werden, einer eindeutigen Beschreibung und Bedeutung. Immerhin konfigurieren die Bilder eine Matrix der Erinnerung, ein Schema, das im Betrachter das Thema sowohl emotional als auch analytisch aufruft und Raum für Reflexion bietet. Indem Spiros Margaris sein Thema mit medien-theoretischen Aspekten kurzschliesst, öffnen sich seine scheinbar schlichten Bilder einem Universum der Spekulation, das letzten Endes sogar philosophische Fragen berührt. Nicht uninteressant wäre es beispielsweise, die Bildserien Spiros Margaris mit der Geschichtsphilosophie Walter Benjamin’s in Beziehung zu setzen. Hatte jener doch ein geradezu photographisch verfasstes, dialektisches Bild, in welchem das Vergangene mit der Gegenwart blitzartig eine sinnstiftende Konstellation eingeht, in das Zentrum seiner geschichtsphilosophischen Überlegungen gestellt, und behauptet, dass eine solche Konstellation stets einer Konstruktion bedarf. – Das wäre dann allerdings ein anderer Text.

Daniel Marzona

Rachel K. Ward, January 2002, Associate Curator, Swiss Institute – Contemporary Art (SI), New York

Memory is a dangerous function. It retrospectively gives meaning to that which did not have any. It retrospectively cancels out the internal illusoriness of events, which was their originality.

– Jean Baudrillard, Cool Memories III, 1991-5, p. 30.

There is at first, a place, a location that has no meaning, no memory, until you arrive there and experience it. And then afterwards, your memory of the place, of the event or events that happened there, replaces your perception of the properties of the location, of your acknowledgement of the place that at first stood alone.

In Spiros Margaris’ work, the viewer is presented with two images. On the left, a photograph of a vacant public space, much like a work by Bernd and Hilla Becher; on the right, the uncanny presentation of the same space a second time but as occupied by an unknown man in a suit. The difference between the two images is obvious, a space vacant and occupied.

The photographic pairs are presented in groups titled, Mein Spielplatz (My Playground) and Schulträume (Dreams of School Days). These titles imply that the work is about the artist’s experiences. For the projects, he chose particular places from his childhood, places of public use. They are the familiar places of shared experience. Presented as vacant they allow for the viewer’s projected memory. But before one can completely indulge in childhood recollections of locations, there is the juxtaposition of Margaris‘ work with the second image. The photographs show a grown man in a suit, a man too large in scale for the childhood spaces, who is dressed for work, not play. This anonymous figure prevents personal projection onto the vacant photographs and suggests some unknown business.

While the artist claims the work is a warmhearted representation of his return to the places of his childhood, one cannot underestimate the images‘ compositions and odd croppings. The man’s torso alone is seen strangely bending down to hold a toy horse, his back faces the camera as he looks at a clock, his legs are shown standing near a slide, his foot extends from a doorway he has just entered. These do not seem like ordinary images of childhood locations revisited by an adult, where for instance, the person concerned stands proudly next to their school’s main entrance or near the now aged elementary teacher. There are no names, no other people, only empty places and an over dressed, obscure man in the shot; a man who seems to be a sort of „nom du pere“ in the schoolyard, ominously turned from the camera or only partially visible, as if he were an investigator on a surveillance assignment.

The man in the photographs, Spiros Margaris, is on a search. In the photographs, he seems to be chasing something through doorways and looking outside. In one shot he is shown running down a staircase, as if he could not find what he was looking for upstairs, and rushing on to other places. He is not searching for the locations of his childhood, but for his childhood. Where did it go? He is in the right place. His first photographs show proof of the locations, but when he tries to fit back into that world, he is the wrong size. The right place at the wrong time. What seems like a science fiction scenario is the reality of age and the passage of time, and of the fascination with the static locations that seem to outlive us.

Margaris‘ images, his initial public offering at professional artwork, have a prominent dialogue with other photographs. His obsession with modest locations compares to recent work by Candida Höfer, a student of the Bechers. Margaris‘ interest in the relationship between the inhabitant and public space follows the lead of Margaris‘ fellow Swiss, Robert Frank. There are also close ties between his work and Sophie Calle’s Hotel Series, in which locations become the subject of repeated consideration. One should also not overlook the similarity between the playground gymnasium in Margaris’ work and minimalist sculpture such as Rachel Harrison’s The Bell Tower. The gymnasium looks like Harrison’s geometric sculpture, which like Margaris‘ work, needs a participant to complete it by pressing the doorbell on one of its bars.

On one side of Margaris‘ work is a world uninhabited, and on the other, a world with one man. Where exactly are these places? Who is the man who inhabits them? What is the complete story? The real story is in the images we cannot see. It is the world before and after nostalgia, the vacant, memory-less place that seems to have nothing but formal properties, and then you live there, and it becomes permanently inhabited, by the persistence of memory.

Rachel K. Ward

Oh My Darlin‘ Clementine is a series in which I try to capture the beauty of a slide, Clementine, with which I had no childhood connection, unlike the trilogy Mein Spielplatz (My Playground), Schulträume (Dreams of School Days) and Die Turnhalle (The Gym).

I happened to pass by her often and my love for her just kept growing to the point I couldn’t be without her. And the only way for me to keep Clementine with me, the way I saw her, was to photograph her with me.

Spiros Margaris

Art explores the way we live.

Work is the most typical source of the means to live.

Work exacts its tribute — in the workplace, we live the greater part of our lives.

In Lost in Taunusanlage 12, I went into that which many people know as the workplace, the corporate complex. Each day, they take their last few breaths of unprocessed air before they go up into great towers or deep into sprawling complexes, in which every corridor, every office, every cubicle, every conference room is similar, if not identical, to every other one, on every other floor, in every other wing.

In this series, I tried to explore the de-humanization, isolation, monotony, fear and disorientation that an individual can feel in these unnatural environments.

The vehicle for my exploration is the action of a dream, my dream, which takes place at twin towers located at Taunusanlage 12 in Frankfurt, the headquarters of Deutsche Bank[1].

I move through the spaces in these twin towers and attempt to orient myself in the space in which I suddenly find myself, where all the floors seem the same, no floor numbers tell me where I am, and as I look out at the tower across from me, I see into an identical space and face my own reflection. There are no street names and no natural landmarks here to guide me.

I am in an artificial new geography, playing the various roles of its inhabitants, who each day must navigate it anew to earn their existence, to redefine and re-exert themselves, and for some, to earn the power over all the others that play within this separate society.

Spiros Margaris

[1] The setting for my exploration here is especially apropos given the unique use to which the bank’s art collection is put within the towers. In an effort to differentiate the identical floor plans and thus to help the buildings’ occupants orient themselves, each floor is dedicated to, and named for, the artist whose work is displayed on that particular floor.

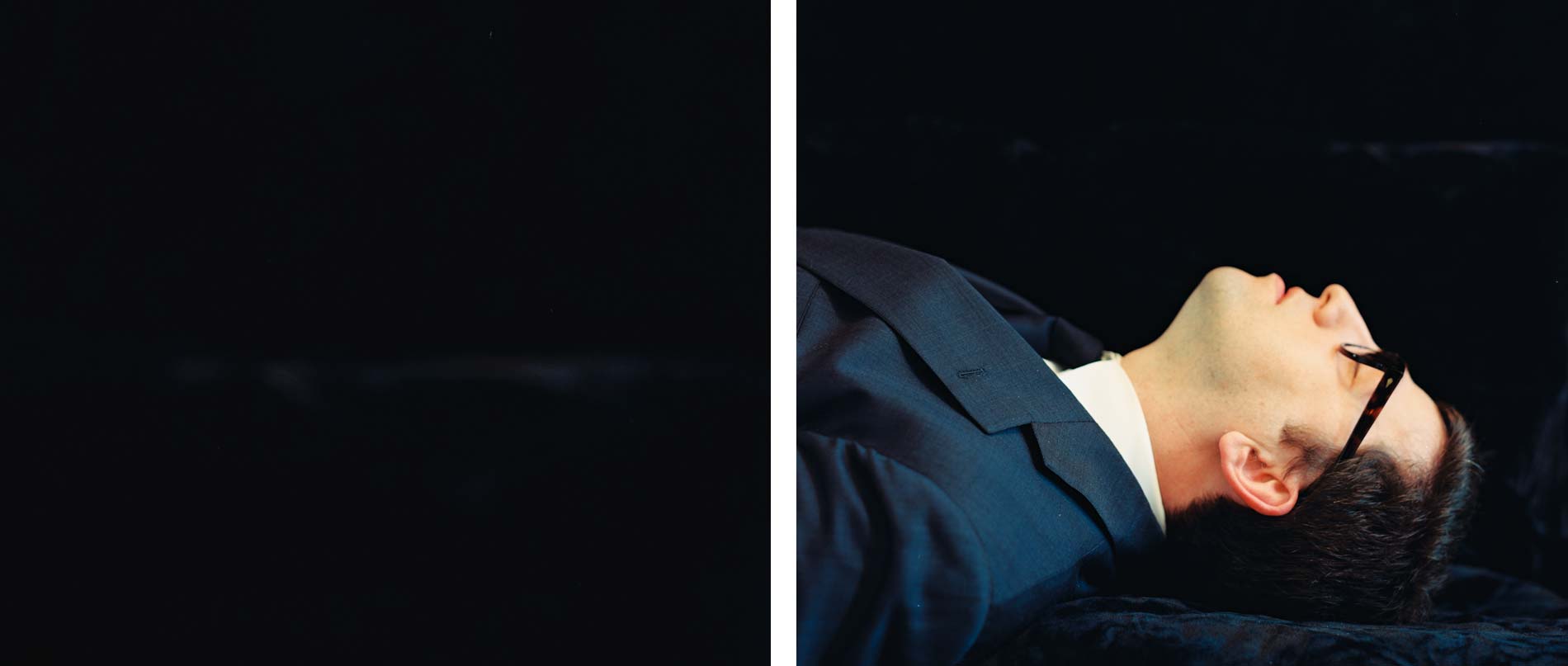

This series is inspired by Gerhard Richter’s series „18. Oktober 1977“, images based upon photographs disseminated by the press regarding the Baader-Meinhof terrorist group.

As Richter based his paintings on photographs from newspapers, magazine clippings, etc., I went FULL CIRCLE. As Richter appropriated photography for his paintings, I appropriated his paintings for my work.

That puts the paintings a step below in the process of my work and by the same token I go full circle to their origins. I am not attempting to compete with Richter’s paintings; the medium of painting has very different expressive strengths and these paintings by Richter in particular have a special, elevated importance as Richter “broke lances” with them – and was punished for it — and made it easier for future artists to deal with this topic. However, bringing the images full circle, back to photography, results in a reevaluation of Richter’s paintings, the issues they raised, and the medium of photography. My photographs don’t attempt to bring more to Richter’s work, but rather to explore the origins of his work, to deconstruct these origins back to their simplest terms, and to re-depict the source of his inspiration.

The art world saw the process of painters being inspired by photographs as some kind of validation of photography as art. I attempt to go one step further and use the paintings to inspire my work.

The figures one sees in some of the photographs are paper cutouts of me (see Arrest 1 (Festnahme 1) B or Funeral (Beerdigung) B). I could have achieved my purpose in a smoother, more verisimilar way with Photoshop, but I intentionally used a cruder method of paper cutouts to bring a freshness to the fakeness of the images in this digital, easily-manipulated world, where people now distrust what they see.

I think it is important constantly to look upon the past with fresh eyes and to use the past to re-evaluate what is happening politically in the world at any given time. For example „Youth Portrait (Jugendbildnis)“, the painting based on the photograph of Ulrike Meinhof portrait, I attempt to raise questions and open dialogues – who is she, why is she being portrayed by the male artist (me), who were the Baader-Meinhof group, …

Spiros Margaris

Du bist nich allein (You are not alone) is a project that was filmed in my home in New Jersey, USA in 2001. For the first time I tried to explore the possibilities of the medium film to express my art in order to give the audience a feeling of a live performance.

I have always been inspired by old cinema, and for that reason, I am leaning not only in inspiration to old cinema but also in the mediums I use for my artworks.

Spiros Margaris

In his series Mein Spielplatz (my playground), Schulträume (dreams of school days) and Die Turnhalle (the gym), Spiros Margaris revisits the spaces that he occupied as a child and attempts to freeze the images and memories of his childhood and adolescence before they are lost forever. Surprisingly, the physical spaces have changed little over the years. Yet, he has changed, and he explores his new relationship, both physical and emotional, to the playground, schoolroom, gym and schoolyard scenes that were once part of his daily reality.

The first step in his exploration is the image of these childhood and adolescent scenes as they now exist without him, and, indeed, devoid of any of their usual inhabitants, the children, the parents, the teachers, etc. The artist’s childhood memories start to flow as he looks upon and becomes an active participant in these once familiar scenes, very much as the childhood memories of author Marcel Proust were triggered years later by the taste of a rusk cracker dipped in tea.

His photographs of empty playgrounds, classrooms and schoolyards are virtually universally familiar scenes of every person’s youth and yet evoke in each viewer the wholly unique remembrances of his or her childhood and adolescence. As Spiros Margaris, and the viewer, looks upon these empty, or objective, images, he fills in the scene with his own memories.

He then moves from the psychological to the physical by occupying these same spaces, challenging and synthesizing his memories with a new reality. The images of the artist as he physically penetrates these spaces are a revelation, a complete transformation and personalization of the objective images. He moves in these spaces as he did when he was a child or youth but now as an adult figure – an aging process manifested not only by his physical size but by the suit and eyeglasses donned by the artist – and with his new adult body comes a new perspective and relationship to these spaces.

The photographs are the combination of a crisp and logical reality and the soft beauty and lyricism of a memory or dream, with all its incongruity.

Spiros Margaris